PRESS

Editors' Roundtable

by Richard Speer

Last month, making the gallery rounds in San Francisco's Minnesota Street Project, I was reminded of the links between art-making, political divisiveness, and the brutal destructiveness of fire. The wildfires that consumed thousands of acres throughout California earlier this year seemed to creep into the Minnesota Street complex by way of artist Monica Lundy's "burn paintings" at Nancy Toomey Fine Art. Lundy, who is based in Los Angeles, harnessed the power of fire in her new body of work, entitled "Deviance: Women in the Asylum in the Fascist Regime." Using candles, cigarette lighters, and kitchen lighters, she singed and scorched her mixed-media paintings of women unjustly institutionalized during the regime of Benito Mussolini (Lundy co-conceived the project with historian Annacarla Valeriano while in residence at the American Academy in Rome). The timing of the exhibition, opening at the end of a historic wildfire season, was coincidental but symbolically pregnant. Fire, as Lundy has written, "is evocative of many things: futility, helplessness, rage, and impermanence. It also has a redemptive quality, carbonizing matter, information, and evidence, reducing and purifying everything to the same state of nothingness."

Taking in the show I was struck by the ways in which fire and the larger phenomenon of oxidation are apropos to our times. As life has gone on since Election Day 2016 and so many of us have become inured to "the new normal" of daily assaults to the pillars of our democracy, it has seemed that even as the underpinnings of civilized society are burning to the ground, many Americans are blithely "fiddling while Rome burns," returning to business as usual and anesthetizing ourselves with the usual distractions: Netflix, celebrity gossip, art openings, social media, and virtual-reality gizmos of sundry stripes. Who will extinguish our civic bonfire, a conflagration personified by a man whose signature phrase for years was "You're fired"?

Because of its universality — we are all oxidizing, after all, decaying down to our very cells — artists have used forms of fire and oxidation as a pictorial tactic for millennia. The patinas that give bronze sculptures their cornucopia of finishes are products of oxidation. The varnishes that painters have long slathered on panels and canvases have oxidized over the centuries, burying once-bright pigments under strata of sepia-toned grime. In the 20th Century, Andy Warhol wryly co-opted the Classical lineage of the patina in his "Oxidation Paintings," notoriously created by urine oxidizing copper-infused paints. In 1970, John Baldessari famously burned his painting output from 1953 through 1966, titling this clearing of the proverbial slate "Cremation Project." Likewise, Gerhard Richter used box cutters and fire to destroy about sixty of his photo-based paintings from the 1960s, among them images of Adolf Hitler and other Nazi-related propaganda. More recently, Dakota tribal elders originally planned to burn artist Sam Durant's controversial wooden installation, "Scaffold," after its ignominious run at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, but later decided to bury it instead, consigning it to a slower form of decay.

Here in the Northwest, at least two artists employ oxidizing processes to "cure" their work. Seattle-based painter Jaq Chartierconducts experiments, which she dubs "tests," by using different paints, stains, dyes, and other media to create sumptuous rows of mutable colors, which sometimes intensify over time and sometimes blanch. Portland-based artist and fashion designer Rio Wrenncreates intricate geometric patterns on silk by letting metals rust onto and into the fabric. In both cases, processes we typically think of as corrosive wind up birthing objects of astonishing beauty.

Similarly, in Lundy's "burn paintings," fetchingly lyrical portraits emerge not only from a destructive element, but also from subject matter that is anything but benign. From the 1920s through the 1940s, the subjects of these images were forcibly committed to the Sant'Antonio Abate, a psychiatric hospital in Teramo, Italy, for the dubious accusation of being "bad fascist women," a sham diagnosis with symptoms variously linked to hysteria, willfulness, and being deemed unsatisfactory wives or daughters by their husbands or families. That the stories of these victims of systemic injustice could emerge as hauntingly beautiful images, brought forth by a scholar's research, an artist's hand, and the transformative effects of flame, is a testament to the redemptive power not only of fire but of aesthetics itself. One can only hope (and also organize, mobilize, and vote) that we in the United States will eventually emerge from our own current trial by fire similarly transformed: scorched, scarred, but ultimately with our principles restored and our moral leadership redeemed.

[The Editor's Roundtable is a column of commentary by our own editors and guest columnists from around the region. Their opinions do not necessarily reflect that of Visual Art Source or its affiliates.]

Monica Lundy @ Nancy Toomey

Posted on 27 August 2018.

by David M. Roth

The old adage about ignorance of history condemning us to repeat it appears to be a driving force behind the work of LA artist Monica Lundy. She’s devoted the past nine years to examining the fates of incarcerated women, turning archival photos into portraits on paper that attempt to reclaim lives marred or destroyed by injustice. The artist previously made paintings of prostitutes derived from early 20thcentury SFPD photos, and other works based on institutional photos of female patients at Stockton State Hospital and inmates at San Quentin Prison. Her last show in this space, based on historic photos of SF’s Fillmore District, featured pictures of Japanese-American residents before they were sent to WWII relocation camps and African-Americans before “redevelopment” pushed them out of the neighborhood.

Her current series, Deviance: Women in the Asylum During the Fascist Regime, employs a similar modus operandi. It’s based on a trove of photos and documents that were exhibited at the Rome Area History Museum under the same title, prefixed with the words Flowers of Evil. Lundy saw the show in 2016 during a six-week artist residency at the American Academy. Her stay subsequently stretched to a year after one of the exhibition’s organizers, Annacarla Valeriano, of the University of Teramo, offered to help her examine the archives of the Sant’Antonio Abate asylum, the psychiatric hospital from which the source photos for this series, made during 20 years of fascist rule (1920 to 1943), were culled. The paintings add a fresh chapter to the artist’s ongoing examination of the dark corners of women’s history.

What justified the incarceration of these innocent women and their barbaric treatment, which included, among many things, the withholding of basic necessities? The most common reason listed on medical records was a condition called “female deviance.” It had nothing to do with mental illness. Records reveal behavioral descriptions such as talkative, unstable, inconsistent,

extravagant, excited, insolent, unruly, impulsive, nervous, erotic, restless, irritable, sensational, red in the face and flirtatious. Today we see this for what it is: men using state power to control women. Attached to each file was an inmate's photograph. Fascists, like Nazis, thought "deviants" possessed common traits and physical characteristics that could be identified and cataloged.

Viewers familiar with Lundy’s work will note striking differences between these paintings and those that came before. Where the surfaces of her portraits of prostitutes consisted of thick accretions of acrylic paint and cinders that resembled geological events coaxed into corporeal form, her Italian asylum paintings, while employing many of the same materials and methods (coffee, ink, mica and selective burning of paper), exhibit none of the former series’ topographic qualities. Lundy continues to build up thick surfaces, but she now scrapes them to near-flatness. Up close, the portraits have the look of pieced-together forensic evidence, the main elements being blotchy stains and burned segments set against yawning tracts of white space. Their fractured, almost apparitional appearance mirrors the photographic process, of forms and shadows emerging from chemical baths that were fouled during development, leaving some information intact, some lost.

Consequently, it’s difficult to establish a sense of who these women really were. We see their identifying physical features clearly enough, but from them all we can do is speculate, noting the expressions they wore at the moment they were captured. And while hairstyles, clothing and skin color do give some indication about where, on the social ladder, these women stood before they were forcibly removed from society, their identities and their emotional lives remain

shrouded. By contrast, Lundy’s highly expressive paintings of prostitutes, through sheer force of their roiling, volcanic surfaces, spill so much information about the subjects’ psychological makeup you can almost feel them as a physical presence. Could the gap between the visible and the unknown in her asylum paintings be bridged? Valeriano, the Italian researcher, uncovered and analyzed 7,000 records from the asylum’s archives. Excerpts from those documents would have made enlightening wall labels.

Here it’s worth noting that Lundy earned her MFA at Mills College and studied with Hung Liu, the Chinese-American painter, who, for decades, has worked from historic photos with the intent of “summoning ghosts.” By dint of the subjects’ surroundings, her paintings offer a lot of social and historical commentary – particularly for viewers versed in 19th and 20th century Chinese history.

For Lundy, who spent her childhood living in a Saudi Arabia, women’s issues have long loomed large. Early on she sensed that the women she lived among were treated as inferiors, held separate and hidden from society. Even as a foreigner, she often experienced these limitations and judgments. As a young girl she also felt the sting of sexual harassment. After that experience, pivoting her attention towards prisoners, prostitutes and patients seemed natural, maybe inevitable.

The relevance of this work seems obvious, and not just for women in underdeveloped countries. While writing this review I came across this headline from the August 26 edition of The New York Times: “Women in Politics Often Must run a Gantlet of Vile Intimidation.” The story reveals that threats of physical violence against female office seekers are now common, so much so they’re now seen as par for the course, like sexual harassment in the workplace. This news, coupled with what we learn from Lundy, points to the unsettling possibility that life for American women under Trump could easily wind up looking a lot like what it was for Italian women under Mussolini.

Our government has already jailed the children of innocent asylum seekers, slow-walked court orders to free them, and scared away countless others from exercising constitutionally protected rights. Meanwhile, chants of “Lock her up!” still resound at Trump rallies. What’s next?

# # #

Deviance: Women in the Asylum During the Fascist Regime @ Nancy Toomey Fine Art, through October 13, 2018. Artist Reception: September 8, 5-7 pm.

About the author:

David M. Roth is the editor and publisher of Squarecylinder.

Artist’s Mobilize: With Liberty and Justice for Some . . . An Exhibition Honoring Immigrants

01/19/2017 10:16 am ET | Updated Jan 20, 2017

IMAGE COURTESY OF WALTER MACIEL GALLERY

Since the election, social media has been flooded with angst about the new political reality of a Trump administration. In light of this new climate, many artists are grappling with the same question artists have answered through the ages. What is their duty? Literally, the definition of art history is the study of objects within their historical context. History is calling, and the question is how best to engage their art with the world in a meaningful way.

Artist, Monica Lundy introduced this very conversation to her peers. Many artists, their families or friends were feeling a part of an increasingly disenfranchised community. A desire to lend their voices, regardless of race, religion, sexual orientation was the sentiment that bound them together. Monica noticed there was a great deal of talk among artists about mobilizing, but no definite plans. In listening to her own calling she set out to give life to this vague notion of doing something to make a difference. Monica recalls,

My head began swimming with ideas, and while I wasn’t sure what the final vision would be I knew I wanted to do a project and rally as many artists as possible to participate. All my colleagues and peers felt the same urgency, and discussions began with fellow artists about what this collaborative project could potentially look like. After many conversations, I arrived at the idea that I wanted the project to celebrate and honor one of the communities under attack by this incoming administration. The notion that our country would threaten mass deportation of immigrants is absurd to me, and hypocritical. After all, this country is a nation of immigrants.

Monica found a kindred spirit in Los Angeles gallerist and friend, Walter Maciel. In his own words, I feel it is my obligation to use my public space and voice to bring attention to the issues that threaten our basic human rights. After the election wore off a bit, I realized I was having the same conversations with friends, family, colleagues and random visitors to my gallery, about our fears and concerns and what could be done to help make a difference. Monica approached me with her idea for the show and I immediately knew I wanted to collaborate.

Together, Monica and Walter co-curated, With Liberty and Justice for Some, an exhibition honoring individual immigrants and their important contributions to American society. The exhibition opened January 7th at Walter Maciel Gallery in Los Angeles. Mounting an exhibition of this scope is usually takes several months of work and planning. The invited artists from San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, Philadelphia, New York and beyond responded overwhelmingly with artwork and within six weeks, over 100 artists sent their work for installation. Each artist contributed an 8”x 8” portrait of an immigrant. This exhibition became a very personal issue for many, reflected in the portraits of family members and friends, each with a narrative of the hard working and generous spirits found in the immigrant community. Some artists chose to feature well known immigrants who have made some significant contribution to American culture.

Continued on huffingtonpost.com

Portraits of an Immigrant-Filled Nation at Walter Maciel Gallery

By Sarah Hotchkiss and Kelly WhalenFEBRUARY 8, 2017

When Bay Area artist Monica Lundy and Los Angeles gallery-owner Walter Maciel organized the massive group exhibition With Liberty and Justice for Some, they had no idea how prescient it was. The show of 113 artists, which opened on Jan. 7 with the highest attendance Maciel has seen in his 11 years of operation, centers around a group of 82 8-by-8-inch portraits of immigrants, arranged to resemble an American flag. The symbolism is unavoidable.

Back when Donald Trump was still the President-elect, long before his Jan. 27 executive order became a flashpoint for pro-immigrant rallies at airports across the nation, Lundy, like many in her artistic community, felt both helpless and determined to do something, anything, in response to Trump’s presidency.

“We wanted the project to be supportive of some of the communities under attack by this incoming administration,” Lundy told KQED Arts. “That Mexicans are being threatened with deportation, and Muslims, of being shut out, it reminds me of the history of bigotry in this country.”

She found a willing partner for the project in Maciel, and the call for portraits of immigrants took shape quickly. Bay Area artists involved in the show include longtime Mills College professor and Chinese-born painter Hung Liu, Phillip Hua, Yulia Pinkusevich, Rodney Ewing, Dave Kim and Soad Kader. Each chose to represent either a close friend or family member, or in the case of Ewing, personal hero and pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey.

Immigrants represented in the 158 portraits on view at Walter Maciel Gallery include well-known figures more regularly defined by their contributions to American society than their foreign birthplaces: former Secretary of State Madeline Albright, Albert Einstein, Stokely Carmichael, Bela Lugosi, and naturalist John Muir.

Alongside the easily recognized faces are the immigrants known only to those who lovingly rendered their portraits: artists’ parents, neighbors, teachers and loved ones. Immigrants are ubiquitous, the portraits emphasize; to delegitimize their presence in the United States would rip apart the very fabric of our democracy.

Putting, as Maciel says, their money where their mouths are, the gallery is donating 30 percent of all artwork sales to the ACLU, The Trevor Project, the Center for Reproductive Rights, Planned Parenthood, the Los Angeles LGBT Center and the San Francisco LGBT Center. Twenty portraits have already sold. “We are using our strength and capabilities to make a statement, but also directly supporting those organizations on the front line of taking on this administration,” says Maciel.

“With Liberty and Justice for Some”

Recommendation by Simone Kussatz

“With Liberty and Justice for Some,” a mega-group show co-curated by artist Monica Lundy and gallery owner Walter Maciel, is a response to the feared and certain upcoming changes under the new President. It consists of about one hundred 8 x 8 inch portraits of immigrants, including prominent individuals such as former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, Albert Einstein, Melania and Frederick Trump, William Penn, and others. It draws attention to the new President’s planned immigration policy, which on the surface only affects illegal and criminal immigrants, but may well have unforeseen consequences for many other immigrants and American citizens. Of course, America has been a land of immigrants from its earliest history, when St. Augustine was founded by the Spanish settlers in 1565, to the English separatists who came here on the Mayflower, to the European and Asian immigrants who arrived during the Gold Rush, to the waves of immigrants who came through Ellis Island prior to the first World War, up to the immigrants arriving from various regions of the world in the present day.

Even though this show doesn’t go deep into immigration history, it succeeds by getting rid of labeling and effectively humanizing immigrants. For who is the immigrant? First, he or she is a human being. Second, they could be persons Americans have now or once had relationships with, whether it is the British and deceased friend of American artist Susan Feldman Tucker, the Italian mother of American artist Virginia Katz, or the German artist Nike Schroeder on her path to receiving dual citizenship. This message is fortified through an installment made up of selected immigrant portraits that take the shape of the American flag. Hence, it says clearly and empathically, "united we stand up for immigrants".

MONICA LUNDY Toomey Tourell Fine Art San Francisco

By Richard Speer, January 2014

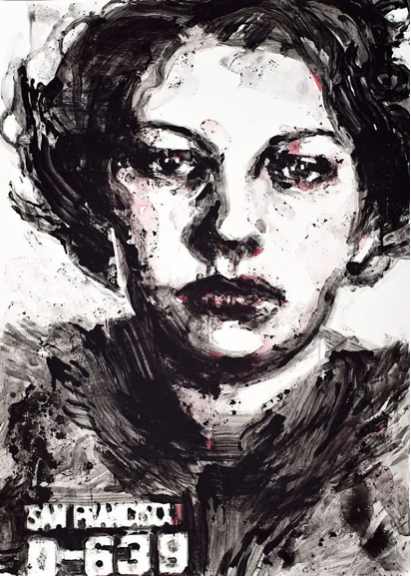

Bay Area artist Monica Lundy beckoned viewers back in time with this haunting exhibition of mixed-media works on paper, “House of the Strange Women”. The show’s enigmatic title was taken from a book Lundy found at the San Francisco Public Library that contained hundreds of mug shots of men and women arrested for prostitution and pimping between 1918 and 1938.

After photographing many of the book’s pages, images of people whose scars and bruises reveal the violence of their difficult lives, Lundy translated them into drawings and paintings on large pieces of heavy paper. Her materials – gouache, pulverized charcoal, coffee grounds, and ink – impart a rough, sooty quality to her artworks that echoes the darkness of their content, but she brightens certain passages with the sparkle of mica flakes. In the nearly seven-foot-tall Vio. Sec 12 (2013), the model’s black eye and facial abrasions are rendered in luxuriantly swelling waves of impasto.

Lundy’s rather visceral method of working also reflects her violent source content. She hurls, smears, and tramples her materials, lending a distressed appearance to the finished products. In 0-3586 (2012), a woman with a handkerchief tied around her hair projects a sultry intelligence that, complemented by the work’s sepia palette, evokes the heavily-lidded vamps of silent films. Smaller pieces such as 0-724 (2013) are not as textural, but their sitters fill the picture planes with a quieter, more ghostly presence.

In previous suites, Lundy has riffed on photographs of late 19th- and early 20th- century prison inmates and mental-hospital patients. This series continued her tack of the esthetic historical excavation, reviving and immortalizing marginalized communities that might otherwise remain invisible.

Monica Lundy @ Toomey Tourell

Posted on 26 October 2013.

Few painters I can think of these days make work that is truly riveting. Monica Lundy, whose specialty is portraiture, joins that select group. Winner, in 2010, of the Jay De Feo MFA Prize at Mills College, Lundy, 39, demonstrates that bravura painting, despite its near-fossilized status in contemporary art, still has the power to stop you in your tracks.

The Oakland artist focuses her attentions on tough characters and tough places: prisoners, mental hospitals, and, in her most recent series, House of the Strange Women, on male and female prostitutes, painted from SFPD photos taken in the ‘20s and ’30s that she discovered in a book of the same title in a public library. Her works, all on paper, do for painting what Dashiell Hammett did for detective fiction. They bring hard-boiled characters to life without judgment and at a scale that borders on cinematic. Her paintings show the accused staring into police cameras looking sad, angry, dejected, defiant or nonchalant. Lundy depicts them with flamboyant neo-expressionist gestures, none of which have the effect of romanticizing, moralizing or even sympathizing. Admittedly, expressivity and objectivity don’t often appear in the same sentence. Yet Lundy’s paintings deliver both, evincing a just-the-facts-ma’am approach in a realm where facts are scare. In the absence of biographical details, her subjects are titled only by booking numbers (and in some cases by day jobs), both of which appeared on the original mug shots and are carried over into the paintings. Working with that information, Lundy makes the unwritten stories of their lives explode in a rose-tinged monochromatic palette that seems to fit our collective notion of what the underbelly of Jazz Age San Francisco looked like.

The works on view appear at various sizes, ranging from small- and medium-sized drawings to works that dominate the room. The largest and most powerful stand 80 inches tall, and by that measure alone they command a certain force. Their real power comes from Lundy’s paint handling. Reproductions can’t describe it, so imagine this scenario: Robert Smithson in a pickup spinning donuts in a mud pit with Anselm Kiefer flinging cinders at the resulting splatter and Ralph Steadman applying, beneath these actions, his trademark red-pink washes. This is, admittedly, a hyperbolic mash-up, but it gets at Lundy’s method.

Oakland painter Monica Lundy, 39, was born in Portland, Ore., but her father's employment meant that she was raised in Saudi Arabia and traveled extensively.

The early experience of feeling captive of an unwelcoming society has informed her artwork, including her current show of unframed mixed-media portraits, "House of the Strange Women" at Toomey Tourell in San Francisco. We spoke in the exhibition.

Q:What's the origin of this series?

A: My work is based on research into obscure histories. The San Francisco Public Library has an amazing historical photo collection, and they presented me a book of SFPD mug shots from 1918 to 1938. These are all people who were arrested for prostitution. And on the outside of the book was handwritten the phrase "House of the Strange Women."

I get really excited when I find these old images that most people don't see, that are fascinating and dark. ... I don't think I would have that same sort of curiosity about a fabricated image.

Q:Why mug shots of women?

A: First of all, growing up in Saudi Arabia, women were second-class citizens. ... And secondly, I was raised under the influence of my grandfather, who ran his family with an iron fist. He was a former master interrogator in Czechoslovakia in World War II. ... He had a file on us grandkids. We'd have to have talks with him and he'd pull out the file and ask us questions - it was a kind of interrogation. So that really influences how I identify with these subjects.

Q:Do you think of these as portraits or more as conceptual art?

A: People often say to me "you've really captured their personalities," but I know nothing about their personalities. ... It's a painting.

People want to be able to understand what they think these personalities were. It's a Rorschach test. ... Some of them resemble the source images and some look quite different but, you know, that's the nature of painting.

If you go

Monica Lundy: House of the Strange Women: Through Nov. 2. 11 a.m.-5:30 p.m. Tuesday-Friday, until 5 p.m. Saturday. Toomey Tourell Fine Art, 49 Geary St., S.F. (415) 989-6444.

Kenneth Baker is The San Francisco Chronicle's art critic

They had day jobs in San Francisco. One was a waitress, another a painter, and another a hotel porter. They wanted to earn more money, so they began selling their bodies for sex. But San Francisco police cracked down on prostitution. That's why these working men and women were forced to face a police camera. And that's why — almost 100 years later — their mug shots were still part of a public record that came to the attention of Oakland artist Monica Lundy. In "House of the Strange Women," on view at Toomey Tourell Fine Art, Lundy brings the mugshots back to life through oversized paintings that reframe the faces of those accused of being whores or pimps.

The people who stare back from Lundy's artwork were in the prime of their lives. Some could pass for movie stars. But Lundy isn't trying to glamorize the alleged sex workers. Even the materials she employs — things like coffee, acrylic gel, and pulverized charcoal — smother her canvases with a viscous density, suggesting that those portrayed had it rough.

"These people were prosecuted in their time for reasons that, in this day and age, may not be reasons to prosecute anyone," says Lundy. "Who do we identify as criminals now? How will that change in the future? We learn a lot about our own culture by looking at how we've marginalized people in the past."

Mugshots, which first emerged in the late 1800s, are now an endemic part of the culture, with hundreds of Internet sites trafficking in arrest photos and paparazzi shots of people under the glare of scandal. It's only the medium that's changed. In far earlier centuries, paintings allowed people to contemplate those accused of criminal behavior, as with Goya's The Third of May 1808, which depicts the French army's imminent execution of an alleged Spanish revolutionary, and Caravaggio's Christ at the Column, which depicts Roman soldiers about to whip Jesus. Whether in oils or in screenshots, these scenes of accused wrongdoers are so often wrenching because we know the legal system can err so badly.

The men and women who Lundy portrays in "House of the Strange Women" were reduced to prison numbers. She found the photos that inspired the work in the San Francisco Public Library. In previous projects, Lundy, 39, has drawn series of women from other eras who were imprisoned at San Quentin and who were committed to a Stockton asylum. The series at Toomey Tourell is her most physical art yet — done Jackson Pollock-style, with Lundy applying material and hovering over the giant canvases as they lay flat on the ground. "I'm literally on the piece — kneeling on it, sitting on it, stepping on it," she says. "It's very messy, and it's very crude, but I feel like that's appropriate to the subject matter. Some of the people in my images were physically beaten up. I used that same kind of energy on the paintings themselves."

Monica Lundy at Ogle Gallery, Portland, Oregon

Review by Richard Speer September 2010

Last autumn, Bay Area artist Monica Lundy began poring through the California State Archives in Sacramento, searching for source material for her impending M.F.A. show at Mills College. Lundy, the recipient of this year’s Jay De Feo Award, came upon a treasure trove of antique books that dovetailed with her fascination for the history of incarceration, particularly the incarceration of women. In volume after brittle, yellowing volume, thousands of mug shots from the late 1800s through the 1930s showed female inmates at the Stockton, California State Mental Hospital and the infamous San Quentin State Prison, where women were interned until 1932. The reasons for the women’s imprisonment ranged from the anachronistic and spurious (“hysteria”) to the sinister (aggravated murder). Haunted by these images, the artist went on to use them as the starting point for several exhibitions, including the current “Obscure Histories.”

Lundy’s gouache-on-paper portraits of the inmates, based on the women’s mug shots and titled after their identification numbers, are laid out in two grids. One of them runs two paintings high by two across, the other three by three, much like prisoners crowded into lineups or cells. While the color palette ranges from drab gunmetal blue to a more harrowing dried-blood sienna, Lundy avoids bleakness by finding the resilience and, yes, the beauty, in each troubled countenance. In works such as “2437,” she exhibits a virtuosity with surface effects, leaving strategic slivers of paper unpainted, such that searing flashes of white blaze up out of the somber eddies of gouache. The technique manages to look both spontaneous and meticulously planned. With her fluid brushstrokes, intuitive compositions, and knack for conveying sumptuousness and sensuality even in the midst of abject sadness, Lundy lets us imagine what a turn-of-the-century portraitist such as John Singer Sargent might have uncovered had he trained his eye on society’s disenfranchised echelons rather than its privileged.

The centerpiece of the exhibition, “Department of Mental Hygiene, 1934,” stretches across the gallery’s expansive south wall. A striking hybrid of painting and sculpture, it is comprised of clay slathered over an armature of nails. Viewed close up, the work is a messy, abstracted topography reminiscent of Anselm Kiefer’s mutant surfaces. At mid-distance, the smears and glops coalesce into human features and garments: a beard, a pair of bushy eyebrows, a nurse’s cap, a doctor’s bow tie. From far remove, the piece’s full impact registers, and the viewer beholds a sepia-tinted group portrait of the doctors and nurses at the Stockton asylum. The cold formality and dread-inducing, proto-Nurse-Ratched efficaciousness of this convocation affords a chilling counterbalance to the vulnerability implied in the prisoner portraits. As the clay dries and cracks over the course of the exhibition’s two-month run, chunks of imagery will flake off the armature, collecting on the floor and leaving ghostly stains on the wall. It all evokes the impermanence of memory and the capacity of photography not so much to capture the fleeting moment, but to embalm it. Across the body of work, Lundy gives voice to generations of women whose voices were silenced first by the penal system, then by death. This is a historically rigorous and emotionally affecting show.

This Week's Top Exhibitions in the Western U.S. (August 17-21, 2010)

Posted: 08/17/2010 8:18 pm EDT Updated: 05/25/2011 5:25 pm EDT

Continuing through September 30, 2010 Ogle Gallery, Portland, Oregon

Last autumn, Bay Area artist Monica Lundy began poring through the California State Archives in Sacramento, searching for source material for her impending M.F.A. show at Mills College. Lundy, the recipient of this year's Jay De Feo Award, came upon a treasure trove of antique books that dovetailed with her fascination for the history of incarceration, particularly the incarceration of women. In volume after brittle, yellowing volume, thousands of mug shots from the late 1800s through the 1930s showed female inmates at the Stockton, California State Mental Hospital and the infamous San Quentin State Prison, where women were interned until 1932. The reasons for the women's imprisonment ranged from the anachronistic and spurious ("hysteria") to the sinister (aggravated murder). Haunted by these images, the artist went on to use them as the starting point for several exhibitions, including the current "Obscure Histories."

Lundy's gouache-on-paper portraits of the inmates, based on the women's mug shots and titled after their identification numbers, are laid out in two grids. One of them runs two paintings high by two across, the other three by three, much like prisoners crowded into lineups or cells. While the color palette ranges from drab gunmetal blue to a more harrowing dried-blood sienna, Lundy avoids bleakness by finding the resilience and, yes, the beauty, in each troubled countenance. In works such as "2437," she exhibits a virtuosity with surface effects, leaving strategic slivers of paper unpainted, such that searing flashes of white blaze up out of the somber eddies of gouache. The technique manages to look both spontaneous and meticulously planned. With her fluid brushstrokes, intuitive compositions, and knack for conveying sumptuousness and sensuality even in the midst of abject sadness, Lundy lets us imagine what a turn-of-the-century portraitist such as John Singer Sargent might have uncovered had he trained his eye on society's disenfranchised echelons rather than its privileged.

The centerpiece of the exhibition, "Department of Mental Hygiene, 1934," stretches across the gallery's expansive south wall. A striking hybrid of painting and sculpture, it is comprised of clay slathered over an armature of nails. Viewed close up, the work is a messy, abstracted topography reminiscent of Anselm Kiefer's mutant surfaces. At mid-distance, the smears and glops coalesce into human features and garments: a beard, a pair of bushy eyebrows, a nurse's cap, a doctor's bow tie. From far remove, the piece's full impact registers, and the viewer beholds a sepia-tinted group portrait of the doctors and nurses at the Stockton asylum. The cold formality and dread-inducing, proto-Nurse-Ratched efficaciousness of this convocation affords a chilling counterbalance to the vulnerability implied in the prisoner portraits. As the clay dries and cracks over the course of the exhibition's two-month run, chunks of imagery will flake off the armature, collecting on the floor and leaving ghostly stains on the wall. It all evokes the impermanence of memory and the capacity of photography not so much to capture the fleeting moment, but to embalm it. Across the body of work, Lundy gives voice to generations of women whose voices were silenced first by the penal system, then by death. This is a historically rigorous and emotionally affecting show.

- Richard Speer